The farms of the future can’t feasibly resemble those of yesteryear in size, shape, or form. In fact, they may not even be on land.

It only takes a few minutes chatting with Bren Smith, Executive Director and founder of GreenWave—the 501c3 non-profit organisation behind a revolutionary new 3D ocean farming technique—to realise this man’s not your typical inventor. He’s humble for starters, and has absolutely no formal science training. Growing up, Smith says he never dreamt he’d wind up where he is today.

‘I’m not as much an environmentalist as a man who wants to spend his life at sea and when faced with the reality that he wouldn’t be able to, did everything in his power to change that,’ says Smith.

Born in the tiny fishing village of Petty Harbor, Newfoundland on the rugged and remote Eastern shore of Canada, at 14 he dropped out of school to join the commercial fishing fleets, subsequently traveling to some of the world’s legendary fishing grounds off the Grand Banks and in the Bering Sea. After decades of work, Smith realised the industry was crashing—the direct result of how humans, like himself, had stripped entire ecosystems of their foundations.

‘The cod stock crashes of the early 90s was my tipping point,’ says Smith. ‘After that, I knew things would never be the same.’

Smith got involved in aquaculture, only to find the practice riddled with the same fundamental flaws as his past line of work. The industrial pallet favoured resource intensive species like salmon, requiring too much feed and chemical use to actually be sustainable.

‘I left disillusioned,’ says Smith, ‘but finally saw that all along the underlying problem was the same. The input per output was simply too great with most species people had committed to for things to work long term.’

Smith next experimented with oyster farming, a species requiring little to no added resources. But hurricanes brought storm-surges, destroying his whole crop. And Smith says with climate changes, he knew such events would only increase in frequency.

‘That’s when I finally realised I needed to get off the bottom,’ says Smith.

Luckily Smith and team’s hard work is seriously starting to pay off. GreenWave’s model and Smith himself have been racking up the awards and financial backers. Last year Smith won the Buckminster Fuller Prize for ecological design, bringing in USD $100,000 to further GreenWave’s plans. And GreenWave’s ever-expanding list of partners includes the likes of big corporations like Google, renowned academic institutions, grassroots NGOs, and government agencies. Smith even did a TED talk in Bermuda back in 2013.

3D Ocean Farming 101

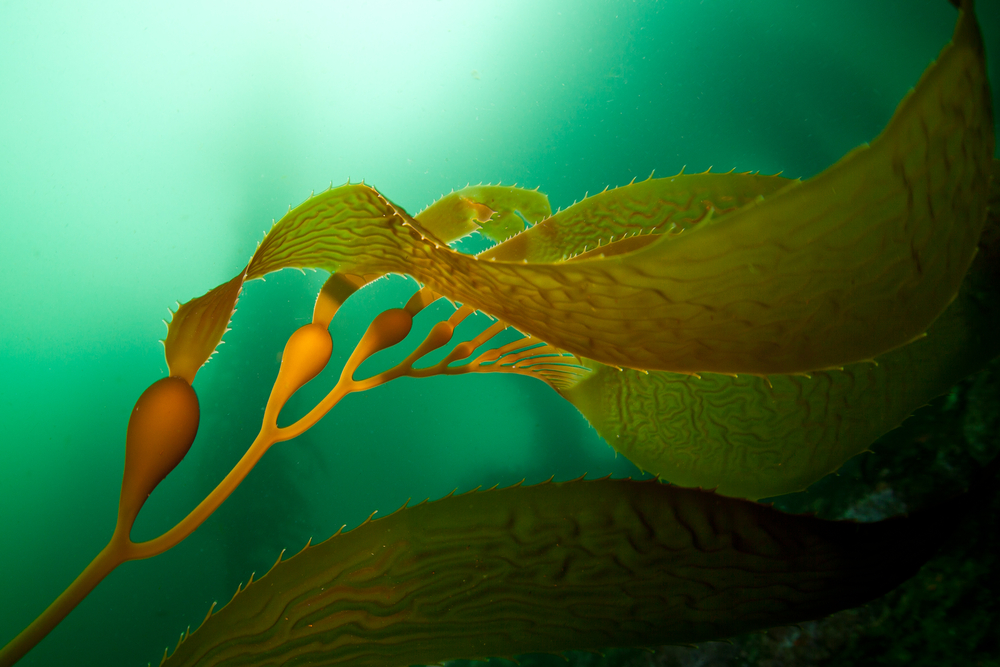

GreenWave’s restorative 3D ocean farming model is the essence of simplicity, the only true inputs being starter kelp seedlings and the physical structure that holds the farm’s critters. You won’t find any heavy machinery on a GreenWave farm. And there’s no need for feed or fertiliser, in stark contrast to most modern-day farms.

Each farm covers 20 acres and is nearly invisible from the water’s surface. Secured to hurricane resistant anchors that sit on the ocean floor, larger corner buoys support rows of rope that run forming a grid across the plot, allowing massive walls of kelp to form. Scallop lantern nets and mussel socks linked to smaller buoys hang vertically alongside the kelp. Oyster, clam, and if so desired, fish cages, lay on the ocean floor below all of this.

Smith says it’s a bit ironic that for most of his life he slaved away on the ocean to make his living, supposedly in the name of efficiency. Now he’s a lazy farmer, Smith chuckles.

‘We’re not working against gravity, and growing a polyculture crop, not hunting or growing a single species,’ he says. ‘Nature itself does most of the heavy lifting.’

Given the simplicity, you’d expect the returns on a GreenWave farm to be less than traditional gigs. But the benefits for those who choose to become so-called blue-green farmers can be large—and extend to the local community, human and otherwise.

‘Per acre, farmers can expect between 10 and 30 tons of greens and around 250,000 tons of shellfish annually,’ says Smith. ‘Especially as resource costs go up, when you begin to break down the profit margins this becomes one of the cheapest to produce foods on the planet. The icing on the cake is it’s also one of the most sustainable food-producing systems imaginable.’

Smith adds GreenWave farms are meant to co-exist with the communities that surround them. People are encouraged to boat and swim around the reef-like networks the ocean farms create. And Smith says fishermen and divers alike favour spots near GreenWave farms for the diversity of fish they draw in.

And the bounties of vertical farms don’t stop here—GreenWave farms produce the raw materials for various forms of agricultural fertiliser, animal feeds, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals and biofuels.

Replicating nature and reaping the benefits

One of the (many) neat things about GreenWave’s model is that it can work in just about any type of marine ecosystem worldwide. That means the variety of species a farm can grow, and number, can vary to meet different habitats, needs, and markets.

Farms use regionally native species, Smith explains, in most North American set-ups this includes a type of sugar kelp, red algae, scallop, clam, oyster, and mussel. Other regional seaweeds are often thrown into the mix.

Once the farm is established, this species-mixture naturally offers a range of ecological services that may indeed be priceless. Seaweeds alongside shellfish work to cycle pollutants out of the water. Kelp and oysters in particular soak up excess nitrogen and other nutrients that cause marine dead zones. Kelps also suck up some five times the C02 as land plants and the reef-like structures they create offer native aquatic species shelter, breeding, and hunting grounds while at the same time working to protect shore side communities from storm surges.

Smith explains all GreenWave farms provide these benefits, but some are actually set in heavily polluted areas to help restore the ecosystem, the products used for non-food uses, namely biofuel. According to their stats, if GreenWave farms took up a space the size of Washington State, they’d produce enough biofuel fodder to meet American conventional oil demand.

Changing the industrial palate

While many people in the West know and love the shellfish grown on GreenWave farms, when it comes to seaweeds, the story’s quite different.

Though the meat-and-bones of commercial marine industries is more focused around larger critters towards the top of the food chain, in the past and many Asian countries, items like sea veggies and shellfish are a staple and have been for generations.

Starting with the popularisation of sushi in North America in the 1970s, kelp has slowly begun inching their way onto more and more plates, though usually in dried forms. But seaweeds have been farmed in Hawaiian waters, where the greens are a traditional food, since the 1980s, when natural stocks became overfished.

Smith says this is a start, but their aspirations aren’t to supply dry products, competing with Asian markets. Instead, they’re championing kelp as a multi-faceted food.

‘I call kelp the gateway drug to sea vegetables,’ says Smith. ‘Kelps are like corn or soy in its amazing versatility. You can use kelps in a wide range of forms, from dry, ground to fresh.’

GreenWave and Smith’s other venture that houses GreenWave’s flagship farm, the Thimble Island Ocean Farm, has been working with chefs to discover ways to cook with kelp and come up with recipes to change people’s conception of the veggie. Kelp noodles, he claims, go great with sauces. Smith’s current favourite? ‘An upscale chef we work with in New York City makes a mean BBQ kelp noodle dish.’

On top of taste and versatility, kelps offer incredible nutritional value. Sugar kelps contain substantial amounts of protein, iodine, calcium, and vitamin C, plus varying amounts of potassium, sulphur, magnesium, chlorine, phosphorus, copper, zinc, and selenium.

It’ll take a lot more work to switch-up peoples’ preferences but some of the groundwork is underway. Some continental North American companies jumped on the bandwagon just before GreenWave, setting up kelp shops to offer people a new form of the ocean greens, like Ocean Approved in Maine, USA. Instead of the freeze dried version most familiar to regional audiences, these groups began selling kelp in the raw, advocating for use of the veggie in meals from breakfast to desert.

‘We need something like a Manhattan Project for sea plants,’ says Smith, explaining there are more than 10,000 edible plant species in our oceans. ‘This should excite chefs and food lovers. Just imagine finding out you’ve been missing out on hundreds of varieties of carrots, rutabagas, and lettuces you never even knew existed.’

Building a global network

Though their progress thus far has been great, Smith says there’s still a long way to go towards fulfilling the dream he and his peers have. One day soon they hope to see a world with healthier oceans and more secure communities, thanks in part to a global network of GreenWave farmers. This may sound like a big ask, but Smith’s vision isn’t as crazy as it sounds. The barriers to entry for 3D ocean farming are relatively few, especially in comparison to traditional agriculture and aquaculture.

‘If you have around [USD] $30,000, a boat, 20 acres of licensed water access, and a willingness to learn, you can be a GreenWave farmer,’ says Smith. To date they’ve been asked to start farms in every major coastal city in North America and about 40 countries worldwide, from South Africa to Trinidad and Romania. At this point, they’re basically trying to keep up with demand while also ramping up research and development to iron out any kinks. Smith says testing farms in warmer climates is big on their agenda.

Meanwhile, at Smith’s other venture, Thimble Island Ocean Farm, there’s also plenty underway. This fall Smith plans to open a community garden, which locals can buy-into and be as hands on as they like.

‘What I find so beautiful about all of this, other than the fact I’ve been given the chance at some form of ecological redemption, is the fact we’re building on an ancient art,’ he says. ‘This is our chance to finally do things right on a global scale for both people and the environment. We’re hoping to be the trigger, then I can disappear on my farm and go back to being a simple farmer.’

Slash-and-burn farming is one of the biggest contributors to deforestation, loss of biodiversity, accelerating climate change and diminishing global food security. In Up In Smoke, one man discovers a solution to replacing destructive slash-and-burn agriculture, but is the world ready to listen? Watch now.

Slash-and-burn farming is one of the biggest contributors to deforestation, loss of biodiversity, accelerating climate change and diminishing global food security. In Up In Smoke, one man discovers a solution to replacing destructive slash-and-burn agriculture, but is the world ready to listen? Watch now.