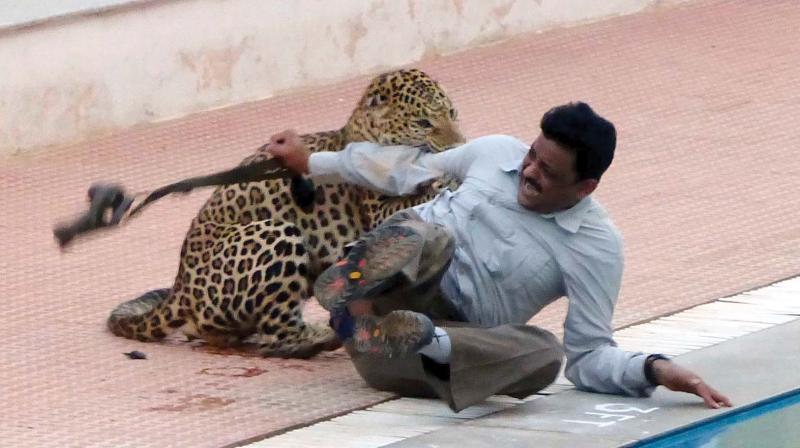

There’s no denying that violent encounters between humans and wild animals make for exciting video content. You might, for example, recall watching on the edge of your seat as men grappled with a leopard at a Bangalore school in this viral video last February.

One of these men—the one that gets bitten on the arm—is Sanjay Gubbi. Gubbi is a scientist for the Nature Conservation Foundation (NCF) and was on the scene helping to tranquillise and remove the agitated animal from the school grounds. Although his injuries were serious enough to warrant hospital treatment, they did nothing to sway Gubbi’s dedication to his goals: conserving wildlife and mitigating human-wildlife conflict in the state of Karnataka. He describes the skirmish as an ‘accident,’ explaining that ‘the panicked leopard was trying to get its way out.’

Unfortunately, sensational videos do nothing to help his cause. ‘The political and public support to wildlife conservation is fast eroding due to various reasons,’ Gubbi observes. Part of this is the occurrence of human-wildlife conflict as well as the resulting media attention and ill-will towards wildlife it reinforces.

In India, a growing human population and expanding cities are setting the scene for conflict by shrinking habitats and bringing people and wildlife into closer contact. While the rate of growth has been slowing since the 1980s, the population continues to increase by 1.2% per year and now exceeds 1.3 billion. The percent of population living in urban areas has increased by 5 percentage points since 2000; Bangalore, for example, grew by 47% between 2001 and 2011 and its limits now abut national parks where leopards and other animals reside.

It is possible that hundreds of leopard-human incidents occur each year in Karnataka alone. A research team led by Dr. Vidya Athreya of the Wildlife Conservation Society found that more than 240 incidents occurred over a 14-month period during 2013-2014. Of those, 32 involved attacks on humans and three resulted in human deaths.

Conflict with elephants is also prevalent. Experts estimate that 100-300 Indians are killed during confrontations with them each year.

The majority of conflicts arise when wild animals prey on livestock or destroy crops. With agriculture representing nearly 50% of total employment in India, rural farmers are a large demographic. Gubbi emphasises that they are the ones most severely impacted by conflict with wildlife.

‘If [crops or livestock are] destroyed overnight by wildlife, they cannot merely walk down to a pizzeria or a fast food joint and order hamburgers and french-fries. There is also a lot preaching by well-heeled conservationists. I often wonder how these relatively wealthy, good intentioned conservationists would feel having tigers, leopards, elephants in their own backyards where their children play?’

It is not uncommon for rural residents to lash back at the animals when their lives and livelihoods are threatened. Roughly 40-50 elephants are killed in India each year through retaliatory actions such as poisoning.

In Gubbi’s estimation, India has been performing relatively well when it comes to conserving endangered species in spite of growing human population and resource utilisation. However he worries that times are changing, and not for the better. ‘In the last decade, new economic policies and changed priorities of decision makers have made wildlife conservation a much more challenging enterprise.’

Reducing conflict will be key to ensuring that wildlife species remain protected. Gubbi has been involved in many initiatives to mitigate human-wildlife conflict and its impacts through his work with NCF: improving government compensation programs for people affected by wildlife, running public information campaigns on how to manage conflict situations, expanding and connecting protected areas and much more.

One of Gubbi’s current priorities is improving working conditions for the frontline staff of state forest departments. They are the ones who put themselves at risk from smugglers, poachers and wild animals as they defend protected areas and help manage conflicts.

‘[These staff] are the cornerstones of wildlife conservation in our country,’ asserts Gubbi. ‘On a day-to-day basis, it is them who can make or break for protecting species that are conservation-dependent. Unfortunately, they are least appreciated, neglected and have little backing. If supported well and led by efficient, benevolent leadership they will turn around marvels for wildlife.’

In Karnataka, NCF was instrumental in establishing an insurance program for the frontline staff hired on a temporary basis, including medical coverage for injuries incurred on the job. Premiums are paid for by the government with revenue generated from tourism within protected areas. ‘I feel it is best to build this into the governmental system so that it can become sustainable,’ says Gubbi. ‘We are currently toiling to get monthly financial benefits, in addition to their salaries, from the government to the frontline staff working in protected areas.’

Each region presents unique conservation challenges, and NCF has introduced innovative solutions to human-wildlife conflict across the subcontinent. South of Karnataka in Tamil Nadu, NCF implemented a system that alerts local residents to the presence of elephants by sending bulk-SMS messages to their cell phones. LED indicator lights, activated when elephants are within one km, were also installed in over 25 visible locations. Because a lack of awareness regarding the whereabouts of elephants was a main cause of conflict in this area, these measures have been highly effective at reducing human and elephant deaths.

In the northern state of Himachal Pradesh, NCF has had success alleviating conflict between herders and snow leopards. An insurance scheme offsetting economic losses from livestock depredation and providing financial incentives to adopt anti-predatory herding methods, in addition to a conservation education programme, has effectively improved attitudes towards predators and stopped their persecution.

Gubbi attributes the success of these initiatives to NCF’s collaborative approach. Many projects would not be possible without the involvement of government and other stakeholders.

‘If we merely criticise and critique the government, political leaders and policy makers, our efforts in any domain of conservation will have little value. If we do not involve ourselves in this complex systemic puzzle, despite several of its limitations, we can pretend to be making a lot of difference to wildlife, but to be honest, it would have done nothing at the end of the day.’

While Gubbi is confident that some wildlife species will be able to thrive living side-by-side with humans, he asserts that ‘there is no one-size-fits-all theory’ and that ‘some species that move over vast distances and have low reproductive rates will need habitats that have very low human densities.’

He also acknowledges that human-wildlife conflict cannot be eradicated completely, but aims to reduce it to a tolerable level. ‘We genuinely need to work towards reducing conflict as it affects lives and livelihoods of people who have been patiently tolerating for several centuries . . . Quick sympathetic response, attractive compensation schemes, working towards improving people’s tolerance towards wildlife, which unfortunately is taking a nosedive in this country, will all be the basis of how conflict can be managed in India’.